The Royal Scot in America, 1933

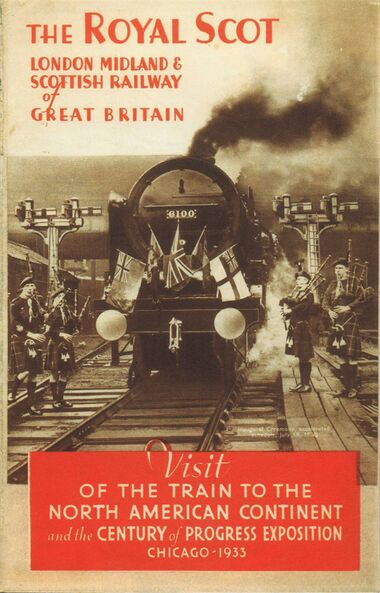

1933: Cover of a leaflet promoting the Royal Scot at Chicago [image info]

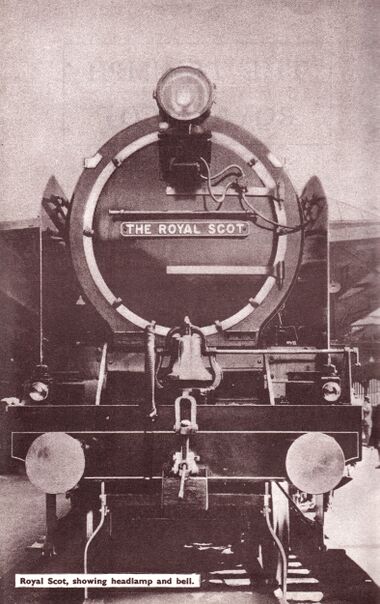

1933: Royal Scot fitted out with a bell and headlamp, ready for the US tour [image info]

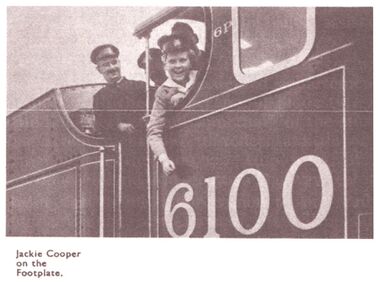

America child actor Jackie Coogan, on the footplate of the Royal Scot [image info]

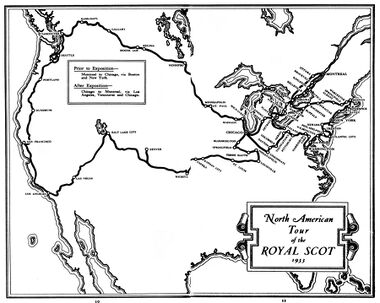

1933 map: North American Tour of the Royal Scot [image info]

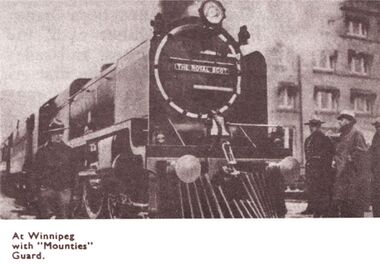

1933: Royal Scot at Winnipeg, Canada, with "Mountie" guard [image info]

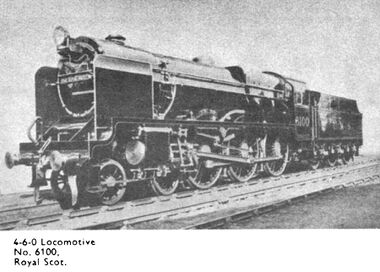

1933: Angled view of the Royal Scot [image info]

The Triumph of the Royal Scot was a booklet produced by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) documenting the Royal Scot train's 1933 publicity tour of the US and Canada, including a period as an exhibit at the 1933 Chicago "A Century of Progress" fair.

The tour was considered a great success, to the extent that after the Royal Scot was replaced by the 1937 Coronation Scot, the LMS repeated the idea with a second US tour in 1939, with a red-and-gold Coronation Scot loco at the head of a new Coronation Scot train.

A big part of the justification for the tour was to promote US/UK relations – Americans would be intrigued by the sight of a British train running on local US track, might be touched by the fact that a British railway company cared enough about what Americans thought to send the train across the Atlantic for the trip (despite the lack of an obvious financial incentive), and seeing the train on person would give them a personal memory and sense of connection to the UK that might stay with them for the rest of their lives.

The potential importance of this feeling of connectedness in the US public became more obvious in 1939 during the followup "Coronation Scot" tour, when US politicians were debating whether or not to supply aid to Britain in the war against Germany - while some Senators were vehemently opposed to providing any form of aid to either side, others might have been swayed by the idea that millions of US voters had apparently come out to see the trains, and that perhaps the US electorate might have more affection for Britain than one might otherwise have supposed.

THE TRIUMPH ΟF ΤΗΕ ROYAL SCOT

The Royal Scot train of the London Midland and Scottish Railway toured the Dominion of Canada and the United States of America from May 1st to November 11th, 1933, covering under her own steam 11,194 miles over railroads of the North American Continent.

During this tour the train was exhibited at 80 cities and towns and was inspected by 3,021,601 people, of whom 2,074,348 passed through the train during its five-months stay at "A Century of Progress" Exposition, Chicago, U.S.A.

Such in bare outline is the story of the Royal Scot's exhibition tour of the North American Continent — a tour which is already destined to remain an event historic in the annals of world transportation. Impressive though they are by virtue of their very magnitude, these cold figures are yet something more. They suggest a little of the romance, the pageantry, indeed the drama that lay behind the great international gesture whereby a complete express train was sent half-way across the globe to be welcomed, feted, and cheered by the English-speaking peoples of the New World. A little slice of Britain transported across the seas — five hundred tons of British science, skill and steel set down for a space among folk who share the same tongue, the same ideals as the men, labouring in workshops 3,000 miles and more away, who fashioned the masterpiece of modern craftsmanship that is The Royal Scot. Never before had a complete British railway train visited the American Continent, much less toured its cities and towns from Montreal to Missouri, from New England to the distant Pacific shores. Every moment of that tour has been one of pride for those associated with it — pride in the skill of the men who could build an engine that would stand up to a climate ranging from 110 degrees in the shade down to eight degrees above zero; pride in the skill of other men who could drive that engine with its eight-coach train up the long spiral grades of the Canadian Rockies to a summit level 5,600 feet above sea level, scorning the pilot assistance required by engines native to the soil.

To say that the tour of The Royal Scot was a great, indeed an unprecedented achievement is to speak with the soft accents of modesty. This little book seeks to tell something of the story of that achievement and to reflect a little of the pride which the 200,000 employees of the London Midland and Scottish Railway feel in it.

But that pride belongs not to one railway company alone, or to its staff. It will be shared by all those who have pride in their own country and have faith in the skill of British craftsmen.

It is a pride that belongs to Britain and to the Empire.

THE BIRTH OF A GREAT IDEA

In April, 1930, as a result of a visit paid by Sir Josiah Stamp, G.B.E., Chairman and President of the LMS Railway, to America and of conversations which he had there with Mr. Rufus Dawes, there was born the idea of The Royal Scot's visit to Canada and the United States and her exhibition at "A Century of Progress Exposition," Chicago.

Transport has always been a most important link in the development of international friendship, and it was considered that no more fitting representative of British transport could be found than The Royal Scot.

In the first place The Royal Scot was regarded as typical of British Railway production; secondly, its daily task of linking England with Scotland automatically created for it a much wider interest than could have been achieved with a train operating only in one country; and thirdly, it has a history going back through 70 years of British railway development, making it eminently suitable as representative of the Nation that gave railways to the World. The proposal to send the train was hailed with approbation on both sides of the Atlantic, particularly as The Royal Scot was the only British exhibit at the Chicago Exposition. In March, 1933, on the eve of the train's departure from this country, the U.S. financial crisis occurred. Despite this, however, the decision to send the train was adhered to, a decision which was greeted with the greatest satisfaction throughout the North American Continent, as affording evidence of British confidence in U.S. ability to triumph over difficulties.

FORMATION OF THE TRAIN

In order that The Royal Scot should be representative of all forms of passenger equipment in this country, as wide a diversity of coaches as possible was chosen, while the engine selected was No. 6100 Royal Scot, precursor of the class of 70 engines of this type, at that time the most powerful used for express duties on the LMS. The eight coaches forming the train were:-

- Third-class Corridor Brake; Third-class Vestibule; Electric Kitchen Car; First-class Corridor Vestibule; First-class Lounge Car; Third-class Sleeping Car; First-class Sleeping Car ; First-class Corridor Brake.

PERSONNEL

Driver William Gilbertson and Fireman John Jackson, both of Carlisle, were chosen to accompany the train and acted as engine crew throughout the tour. At a later stage when it was decided to make an extended post-Exposition tour, Fireman Tom Blackett also of Carlisle was sent out to act as relief engineman. Fitter William Clifford Woods, of Crewe, accompanied the train throughout the tour. In addition, Mr. C.O.D. Anderson was appointed to take charge of the train from a technical point of view and Mr. T.C. Byrom from an operating standpoint and as liaison officer.

SHIPMENT

The Canadian Pacific Steamship "Beaverdale" was chartered for the voyage West, and on April 5th, 1933, the intricate task of loading the train on shipboard was begun at Tilbury Docks, the engine and coaches having been previously prepared for the great adventure at the Company's works at Crewe and Derby respectively. The locomotive was stowed in the hold of the vessel in three sections, while the eight coaches were firmly secured on deck, four aft and four forward. They were preserved against exposure on the voyage by a special protective coating of wax preparation. The world's largest floating crane, "London Mammoth" was utilised in loading the train, and on April 11th, the S.S. "Beaverdale" cleared the Port of London outward bound for Montreal with her precious cargo.

ARRIVAL IN CANADA

On April 21st, the "Beaverdale" arrived at Montreal after an uneventful voyage. The work of unloading was quickly performed and on April 30th, running trials were successfully completed after the engine and coaches had been assembled at the Angus shops of the Canadian Pacific Railway. On her initial trip on "foreign" soil, The Royal Scot attained a speed of 75 m.p.h.

The ovation accorded to the train on her arrival, both from the press and the public, was stupendous, and before the official time commenced thousands of people lined the railway to see the train make its test run.

THE TOUR – A TRIUMPHAL PROGRESS

On May 1st The Royal Scot began her Exhibition at Windsor Station, Montreal, over 18,500 people viewing the train. As she steamed out of the station for her next point of call, Ottawa, thousands lined the platforms and the railroad track outside the City. In both Canada and the United States, the welcome accorded the train can only be described as tremendous. The official total of 531,330 people who inspected the train from May 1st to 24th represents possibly only about 10% of the people who actually saw it during the pre-Exposition tour.

A report from Canada states that "thousands left their beds early in the morning to view the spectacle of an English train rushing over Canadian soil." Another report says "Huge crowds thronged the little wayside stations along the road and cheered as with a flash of maroon the flier whistled its way past."

At times, so great was the number of people which had gathered alongside, and even on the railway tracks, that the driver had to slow down to 15 m.p.h. lest he might run over the more venturesome of those who eagerly pressed forward to view the train. At certain points en route schools were given half-holidays to enable them to see the train.

On May 4th when the train crossed from Canada into the United States, 10,000 people waited at midnight in pouring rain at Niagara Falls station to see her go through.

Everywhere The Royal Scot was greeted with scenes of wild enthusiasm. Crowds turned away again and again—82,770 people inspecting the train in New York to the skirl of the bagpipes— the press of the crowd necessitating the premature closing of the exhibition at Hamilton— motor car hooters, factory sirens shrieking a discordant salute to the passing train—these are just a few incidents in the tour.

Owing to the date of the Century of Progress Exposition being advanced, the pre-exhibition tour of the train had to be curtailed, and after exhibition at Cincinnati on May 24th she proceeded direct to Chicago. Up to and including the Cincinnati visit the train had covered 2,329 miles over Canadian and U.S. railroads and had been exhibited at 30 cities and towns, a total of 531,330 people inspecting the train at these places.

CHICAGO "A CENTURY OF PROGRESS"

The Royal Scot arrived in the Fair Grounds at Chicago at 5.56 a.m. on the 25th May, four minutes before her scheduled time. She had completed her first itinerary with complete success and without necessitating assistance at any point of the somewhat arduous stretches of railway she had covered, a striking testimony to the efficiency of the train.

The Exposition was opened on the 25th May and from the start The Royal Scot proved a major attraction. On the first day 17,227 persons passed through the train, and on August 3rd the millionth visitor since the train had been on exhibition was received. The occasion was marked by the presentation of an oil painting depicting The Royal Scot and Burlington Railroad trains (which were exhibited alongside each other) to the millionth visitor, Miss Caroline M. Pierce of Massachusetts. The painting was autographed by Sir Josiah Stamp, G.B.E., on behalf of the LMS Railway and by Mr. Ralph Budd, President of the Burlington Railroad; the latter made the presentation.

Original arrangements had been for the train to return to this country immediately after the close of the Chicago Exposition, taking a more or less direct route from the "Windy City" to Montreal, with exhibitions at intermediate points. But as the Exposition drew towards a close, more and more insistent became requests for the train to visit a large number of cities and towns in all parts of Canada and the U.S. which it had not been possible to cover on the original itinerary. So numerous were these requests that, in deference to the enthusiasm throughout the two Nations, it was decided that the train should embark upon a post-Exposition tour embracing 41 additional places and covering a further 8,562 miles over Canadian and U.S. railroads.

FAREWELL, CHICAGO!

This "request" tour was only made possible by the close co-operation of the railroads concerned, and with the permission of the Exposition authorities for The Royal Scot to leave Chicago before the actual closing of the World's Fair.

On October 11th, 1933, therefore, The Royal Scot pulled out of Chicago on her "farewell" tour, accompanied for the first 40 miles of her journey by the famous Burlington Flyer express.

A total of 2,074,348 people had inspected the train during its five months’ stay at the Century of Progress Exposition.

FROM SUMMER HEAT TO WINTER SNOW

Exacting as had been the original tour from Montreal to Chicago, it was completely eclipsed in its arduous nature by the post-Exposition circuit. In its long journey right down to the Pacific Coast at San Francisco, and then back northward over the American and Canadian Rockies into Canada, the train had to contend with severe and prolonged mountain gradients, and with extremes of climate such as no British train has ever previously had to face. The maximum temperature encountered was 110 degrees in the shade at Las Vegas (Colorado), the minimum only eight degrees above zero on the final stages of the journey to Montreal. Yet The Royal Scot engine faced torrid heat and raging blizzards with equal imperturbability and efficiency. That efficiency is epitomised in the words of Driver Gilbertson as he closed the throttle for the last time when the train entered Montreal in the teeth of a snowstorm on November 11th, two minutes ahead of time:

"We took a whole truckful of spare parts and we haven't used one."

Space will permit the quotation of only a few picturesque incidents from the final tour.

Everywhere the enthusiasm shown towards the train rivalled that displayed on the original circuit. At Bloomington (Ill.) on October 11th, half-a-mile of pennies were laid on the tracks to be crushed by her mighty wheels and subsequently cherished as souvenirs.

Going over the Colorado Mountains en route from Pueblo to Denver, The Royal Scot locomotive astounded American observers by climbing to the 6,100 ft. Summit with her train of eight coaches without the aid of a pilot engine. The gradients on this journey average 1 in 67 for 25 miles and are steeper and very much longer than those encountered on the train's regular run from Euston to Glasgow.

"GOOD OLD ENGLAND"

Hollywood film stars, including Diana Wynyard (of "Cavalcade" fame), Jackie Cooper and Muriel Evans held a breakfast party on board the train when it visited Los Angeles. When the train left San Francisco (October 23rd), it was accompanied out of town by processions of motor cars and enthusiastic crowds, riding on every kind of vehicle, yelling "Good Old England!"

When the train re-entered Empire territory the enthusiasm which greeted it knew no bounds, and although it was pouring with rain at Vancouver (October 27th) the crowds were so great that extra police had to be called out, and 6,000 people were turned away disappointed.

Typical of the enthusiasm displayed at even the tiniest places on the route was that at the hamlet of Revelstoke (B.C.), through which the train passed on a Sunday, and where the hours of church services were altered so that inhabitants might catch a glimpse of the train.

The Royal Scot locomotive evoked fresh praise on the journey over the Canadian Rockies, when she hauled the train unaided over the steep spiral mountain gradients to a height of 5,600 feet above sea level—a section on which all American trains are double-headed, i.e., employ a second engine.

THE LAST LAP

Through Winnipeg, Minneapolis and St. Paul The Royal Scot entered on the last lap of her long and historic journey. November 11th was the last day of the tour. The train was on exhibition on that date at Kingston, Ontario, where the three-millionth visitor passed through the train. Later the same day the train steamed into Montreal and her wheels rolled to a stop at the end of her long tour. Snowstorms had been frequent all through Canada, and at Montreal there was a foot of snow on the ground.

Windsor Station, Montreal, where the tour ended, witnessed what was perhaps the most dramatic moment of all. It was Armistice Day. Driver Gilbertson's first action on stepping down from his cab was to lay a wreath on the Canadian Pacific Railway's war memorial— tribute from L. M S Railwaymen to their fellow rail workers of Canada who made the supreme sacrifice in the Great War.

HOMEWARD BOUND

After being prepared for shipment at the Angus Shops, the engine and train were loaded on board the S.S. "Beaverdale" in which the outward voyage had been made, and at 7 a.m. on Friday, November 24th, the "Beaverdale" cast off from Montreal and sailed down the St. Lawrence—already in the first grip of winter ice —on the first stage of the long voyage Home.

— LMS , The Triumph of the Royal Scot , (LMS)