Category:R101 Airship

1930: Secrttion Masthead for "Air News", Meccano Magazine, June [image info]

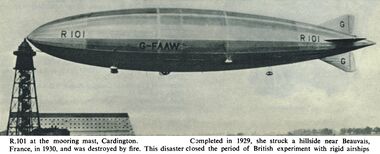

1930: The R101, moored [image info]

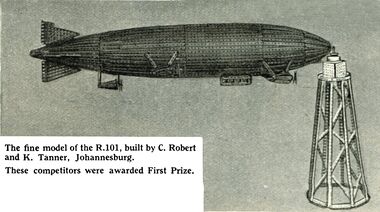

1931: prizewinning Meccano model [image info]

The R.101 Airship was the British airship industry's equivalent of the Titanic, a high-profile project with a prestigious launch, whose managers cut corners and refused to allow the project to be delayed, and which consequently turned into an utter disaster on its maiden voyage, with the deaths of almost everyone concerned. In the the case of the R.101, the disaster was even more complete (and more Darwinian) in that the people who made the bad decisions were actually onboard and perished along with the airship.

Background

The R.101, along with its sister-ship the smaller R.100, were products of the Imperial Airship Scheme, which would allow luxury travel, point-to-point, across the Empire. To spread risk and placate all interested parties, the scheme involved building two airships to two different independent sets of plans, with two design teams, one run by private enterprise (with government money), and one under direct government control. The "private enterprise" airship R.100 was to be conservative in its design, where the "government" airship R.101 was to explore new technologies (for airships), such as servo-controlled steering surfaces and diesel engines.

1928: Things to Come

BRITAIN'S new wonder airships, the R 100 and the R 101, are designed to bring Australia within ten days of London, and to carry, at need, war 'planes to the defence of any threatened part of the Empire.

They bring us to the threshold of the Aerial Age and the dreams of imaginative writers are outstripped by reality. Even Jules Verne never foretold the coming of vast air-liners that, lifted by 5,000,000 cubic feet of gas, and carrying one hundred passengers swiftly through the day and on through the night, would be able to span the Atlantic in fifty hours, and bring the farthest outpost of our Empire nearer to London than was Edinburgh two centuries ago.

...

The vast dirigibles, R 100 and R 101, are veritable aerial hotels. The R 101, 730 feet long and driven at more than the speed of an express train by five 600 horse-power engines, has accommodation on two decks, built inside its vast hull of stainless steel, for one hundred passengers. On the upper deck is a luxurious lounge; a dining-room to seat fifty at a time, where five- and six-course meals can be served; and a number of two- and four-berth cabins. There are two long promenade walks, one on each side of the great hull.

On the lower deck passengers will find the smoking-lounge, the kitchens, a lift leading to the dining-room above, the crew's quarters, and the rest of the passenger cabins. There are shower-baths, a room for dancing, and games courts. Passengers will be able to listen on headphones and loudspeakers to the concerts broadcast by the radio stations over which the great airship flies. A small newspaper, produced on board the vessel, will inform passengers daily of the course of world events.

Thus, from the first crude, almost laughable, "controllable balloons" have evolved, or will shortly evolve, splendid queens of the air, worthy to rank with the Mauretania and other magnificent ocean liners.

Most of this amazing evolution has taken place in the brief period of little more than a quarter of a century. We cannot doubt that the future holds even more wonderful developments, and that the day will come when R 101 will seem as crude and inefficient as the first trans-Atlantic paddle steamers seem to us to-day.

— , E.C. Bowyer, , ~1928

1930: The R.101 Disaster

In 1924 the British Government framed a new airship policy. It was decided to construct two airships, to be known as the R.100 and the R.101, the former to be built by the Airship Guarantee Company, and the latter at the Royal Airship Works, Cardington. The two ships were to be larger than any hitherto constructed, and were to represent a considerable advance in design by increase in size, carrying capacity and speed, the aim being to explore thoroughly the possibilities of lighter-than-air transport on a commercial basis. They were not completed until 1929, but it is convenient to record here the conclusion of the experiments, because they terminated — for the time being anyhow — airship development in this country. During October 1930 preparations were made for a maiden voyage to India, with the intention of exploring the possibilities of a regular commercial air service on that route – a voyage which ended in a tragic disaster, as grievous as any in the history of airship development. The R.101 set out from Cardington, Bedfordshire, on October 5, and the airship carried, in addition to the crew, a distinguished company as passengers, including the Secretary of State for Air, Lord Thomson, all of whom perished. When near Beauvais, France, the airship was forced down, due to leakage of gas, crashed, and took fire, the only survivors being six members of the crew. As a result of the disaster, and the findings of the official court of inquiry, the government programme for airship development was considerably curtailed, though it was decided to retain the R.100 in commission for further experimental work.

— , M.J.B. Davy, , Interpretative History of Flight, , 1937

The R.100 vs the R.101

There seems to have been little love lost between the R.100 and R.101 teams:

- The R.101 team seem to have considered themselves to be the "proper" airship, bigger and better and more ambitious, and with the government behind them. They were the trailblazers, and were going to be running commercial flights to India, which the R100 couldn't initially do because of its petrol engines (petrol being too flammable in tropical temperatures). While the more conservatively-designed R.100 was intended to be upgraded to diesel engines after the R.101 had got the bugs out of the technology as applied to airships (including perfecting the use of new lighter castings), it was the R.101 that was doing the "heavy lifting" with regard to developing the technology.

- The R.100 team seems to have considered the larger airship project to be incompetently run, with political interference and an indecent emphasis on publicity stunts at the expense of safety testing. The people running the larger project seemed to be irresponsible, and were being egged on by a director who was a politician rather than an engineer (as opposed to the R.100 project that was being run by Barnes Wallis, with Neville Shute checking the calculations).

The R.100 team's assessment of the other team as irresponsible seemed to be borne out when the larger ship's maiden voyage turned out to be a lethal disaster that also destroyed the future of the R.100, and the future of airships manufacture in the UK altogether – it would be difficult for the R.100 team to not feel bitter that their own project was cancelled because of problems with their competitor's airship, which were not their fault, and which they had no control over.

The R.100 team got their revenge when their "Chief Calculator" (who happened to also be a novelist in his spare time), wrote a scathing obituary of the project. Neville Shute did, however, acknowledge afterwards that some of his criticisms might not have been quite fair – the R101 team hadn't been in a position to complain or ask for certain details to be corrected, as they'd been killed in the crash.

The Titanic of the skies

The R.101 project had a number of problems, any one or two of which should have made anyone familiar with the accident rate of airships think twice about flying in it.

- The design was experimental.

- Although issues with the engines and the servo control system (which ended up not being used), and a number of other new systems probably didn't contribute directly to the crash, the time and effort spent trying to get those things to work in time may have detracted from the attention spent on making the R.101 a good airship.

- The skin didn't stick properly.

- When designing the R.100 and R.101, it was realised that using fewer longitudinal struts, so that the airship's cross-section was more polygonal and less circular, didn't seem to make the airship's wind resistance appreciably worse. Since using fewer struts simplified the stress calculations, it was felt to be a Good Idea (which is why the R.100 looks so angular). Unfortunately, with fewer struts, each panel of the outer envelope was bigger, and more prone to being lifted off its supporting framework by low-pressure wind effects. Consequently, the skins of the R.100 and R.101 had a tendency to ripple in the wind and tear.

- The R.101 had disappointing performance.

- The larger R.101 actually turned out to have a lower speed and less lifting power than its smaller sibling, the R.100, suggesting that the design was perhaps not as good as it should have been ("a 'bad' airship"). This then set the scene for further compromises:

- The design was "messed-with".

- The ship that was flown was not the same as the ship that was designed. To improve the disappointing lifting capacity, an extra middle section and gasbag was added. This suggests that the final airship would have not have had as large margins for error as the original design. Engineering safety margins are critically important on airships, for a design team to start eating into those safety margins with modifications is a "red flag".

- The operating rules went ""off-spec".

- Rigid airships typically have soft, delicate gasbags held in a rigid structural cradle, all enclosed by a protective skin. In an attempt to get extra lift, the R.101 gasbags were "let out" and allowed to increase in size and capacity by bulging our further between the framework than originally intended. This potentially allowed the gasbags to come into contact with spikey bolts and other protruding parts that were never supposed to be in reach of the gasbag surfaces, and be ripped open.

- Proper safety inspections were made more difficult.

- The solution to the tearing problem was to pack cloth or other soft packing material between the framework and the gasbags. Unfortunately, this meant that it was no longer possible to carry out visual safety checks of the gabags where they were in contact with the framework, to check for chafing. Downgrading the ability to do basic safety checks is another red flag.

- The team didn't accept outside help when offered.

- When Doctor Eckener of the Zeppelin organisation visited, and saw the gasbag situation, he was so alarmed that he offered the services of his team, presumably recognising that any disaster befalling the R.101 would be bad for the whole airship community. When his offer was communicated, it was politely turned down. The Royal Airship Works , working on a project of national prestige, didn't need outside help from Germans.

- Insufficient oversight (#1).

- The people who gave the green light to flight operations weren't able to check the calculations to see if they were reasonable. This meant that whoever was calculating the aircraft's stresses and strains and safety margins, based on optimistic or pessimistic assumptions, was effectively "signing off" their own work.

- Insufficient oversight (#2).

- The "Certificate of Airworthiness" was fudged. When the inspector responsible for administering the "Permit to Fly" informed his boss' boss that he would not be able to sign off on an extension or on a Certificate, his superior consulted the airship programme's deputy as a technical advisor, and was reassured that the problems weren't serious. In effect, the project's safety assessment was self-certified.

- The team was under pressure to get results.

- The competing R.100 had just successfully made the world's first transatlantic round trip, and the R.101 team may have felt that they needed a success, quickly, to prevent their project being cancelled in favour of the Vickers project.

- Lord Thomson appears to have been an idiot.

- We have a message from Thomson "insisting" that the flight go ahead as planned with no further delays, as he'd now finalised his itinerary. This is not a good basis for making safety decisions. In effect, the person in charge was forbidding the airship trip to be delayed even if there were safety concerns.

Overall, the R.101 is a classical example of how not to run a technology project, to the extent that NASA actually have a worksheet dedicated to the R.101, using it as a teaching example of the types of mistake that technology project managers need to avoid.

Meccano Magazine "News"

Enlargement of the "R101"

A new gas bag is to be fitted to the State airship, "R101". The new bag will contain about 500,000 cubic feet of gas, and the addition of the new frame-section that will be required to accommodate it will increase the total length of the ship to 800 feet. The bag will bring the total capacity of the vessel up to 5,500,000 cubic feet, and thus it will be the largest airship in the world, until the completion of the U.S. Navy airship "ZRS-4."

— , "Air News", , Meccano Magazine, , March 1930

"R100" Not to be Flown In the Tropics

According to the Under-Secretary for Air, the British airship "R100" is not regarded as suitable for use in tropical climates because she is equipped with petrol engines, and for this reason her sphere of operations will be restricted to the northern latitudes. The sister ship "R101" is fitted with compression ignition engines, in which fuel with a higher flash-point is used. As yet these engines are in the experimental stage, however, and it is not proposed to install them in "R100" until definite proofs of their efficiency are obtained.

— , "Air News", , Meccano Magazine, , May 1930

Total Cost of "R101"

In view of the many conflicting statements that have been made regarding the cost of "R101", it is interesting to find that up to 31st March, 1930, the total expenditure on this vessel was only £603,500. This sum includes the cost of power plant, experimental engines, overhead charges, shed and flight trials, running repairs, modifications and maintenance, in addition to the initial cost of design and construction.

— , "Air News", , Meccano Magazine, , June 1930

"R 101"

I am sure my readers would not wish me to pass over in silence the tragic end of "R 101." I do not propose to enter into any of the details of this terrible disaster, for these are now familiar to everybody. The two outstanding features of the tragedy are its utter unexpectedness, and the fact that at one blow it removed so many prominent men connected with the development of air transport. Such men as Lord Thomson, Air Minister; Sir Sefton Brancker, Director of Civil Aviation; and Major G. H. Scott, Assistant Director of Airship Development, will be hard to replace.

One of the results of the disaster has been the raising in some quarters of a demand that experimental work in connection with airships should be abandoned. This demand is natural, but it is one that will have no effect. When the" Titanic" went down the same kind of people said that there must be no more giant liners; yet steamship development has gone on, and bigger and faster liners are now crossing the Atlantic.

Progress cannot be stayed by disasters, however great. Airship development must go steadily forward, and the sacrifice of those who perished in "R 101" will not have been in vain.

— , "Air News", , Meccano Magazine, , November 1930

Media in category ‘R101 Airship’

The following 3 files are in this category, out of 3 total.

- Meccano model of the R101 airship (MM 1931-05).jpg 3,000 × 1,672; 860 KB

- R101 airship G-FAAW, 1930 (BA2 1944).jpg 3,000 × 1,217; 708 KB

- R101 airship G-FAAW, Air News (MM 1930-06).jpg 3,000 × 854; 567 KB