The History of the Pullman Car (TRM 1898)

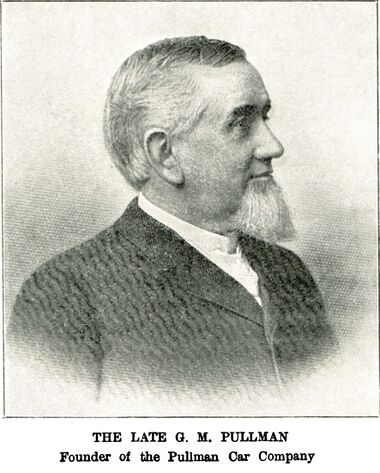

The Late G.M. Pullman, Founder [image info]

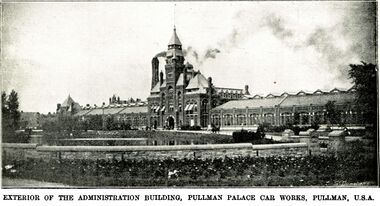

Exterior of the Administration Building, Pullman, Illinois [image info]

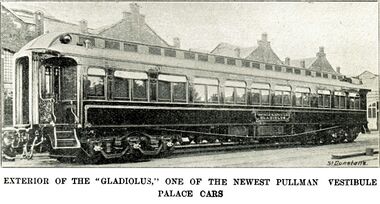

"Gladiolus" Palace Car [image info]

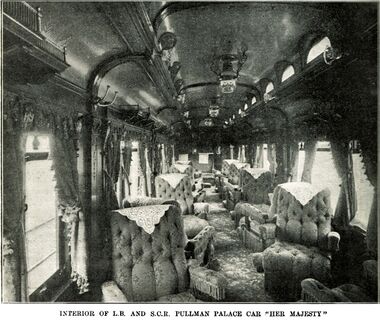

"Her Majesty" Pullman Place Car, LBSCR [image info]

J.S. Marks, Director and European Manager [image info]

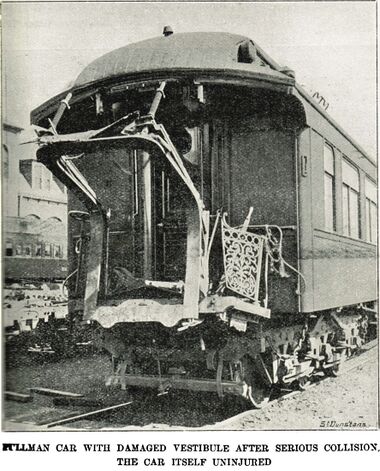

Damaged Pullman vestibule, carriage unharmed [image info]

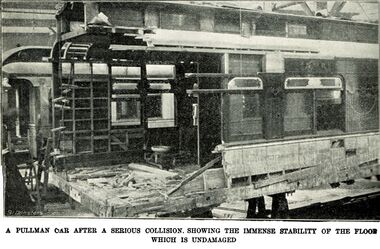

Pullman Car after serious collision, floor unharmed [image info]

Pullman article, in the 1898 volume of The Railway Magazine, pages 376-383.

THE HISTORY OF THE PULLMAN CAR

By "Wanderer"

THE Pullman Palace Car Company must always be regarded as the pioneers of palatial railway travelling. It was in the mind of Mr. George Mortimer Pullman that the idea of an hotel car first originated, and it was under his personal direction, and owing to his steady perseverance that, twenty years ago, such cars established their superiority over all other railway stock. Mr. Pullman had the satisfaction of seeing his handiwork appreciated, not merely in his native country, but in nearly every part of the globe, and, where his own cars have not actually appeared, their very existence elsewhere has led to unmistakable improvement in the character of passenger accommodation of all kinds.

America was appropriately the home of the Pullman. Railway development in the United States began with the importation from England in the "twenties" of three locomotives, built in the crude style of that time, bearing not the slightest resemblance to the enormous engines which are now seen upon the American railroads. Our cousins across the Atlantic were not long, indeed, before they began to alter the British patterns, and their progress in locomotive building was equalled by that in coach construction. The rapid extension of the railway system of the United States between 1830 and 1854 opened out routes of great length and called for stock different from that which was sufficient for local traffic. Mr. Pullman recognised this necessity as a young man when he was engaged in the task of bodily removing brick and stone buildings, and boldly determined to devise the sort of coach which seemed to be necessary.

A "sleeping-car" had made its appearance on some of the American railroads, but in point of comfort it bore about the same relation to the modern Pullman as the old ship's mattress did to the deck cabin in the steamers of the present time. A sixty-mile journey completed in one of the sleeping berths which were in use in the year 1858 confirmed Mr. Pullman in the opinions which he had formed in earlier years, and led him to resolve upon vigorous action. He began operations in the following year by converting into sleeping cars two old-fashioned coaches which had long been doing service on the Chicago and Alton road. Inadequate as these were to satisfy his ambition, they were much approved, and gave the public a zest for something even better. Mr. Pullman's designs gradually advanced, and in 1863 he began in Chicago the construction of an entirely new car. The outcome of his efforts was the "Pioneer," which he produced in spite of the fact that he had not enjoyed the advantage of any mechanical training. But he gathered in his little workshop a body of skilled artisans who were fired by his enthusiasm, and loyally co-operated with him at every stage of construction.

The "Pioneer" was totally unlike any car which had been seen on the American railroads, but it was a costly production, and there were croakers who said that on this ground it could never come into general use. Up to that moment no company had dared to spend more than four thousand dollars on a single first-class sleeping car, but the "Pioneer" involved an expenditure of eighteen thousand dollars! The new car was built on an entirely original model, combining larger proportions than those previously attempted, massive strength of structure, and rich internal fittings on an elaborate scale. Indeed, the decorations were so beautiful that some critics said they were too good for the passengers! It was predicted that travellers, unaccustomed to such luxury as the car supplied, would not stop to remove their boots before entering the comfortable beds, and that they would commit other indiscretions equally unpardonable. All such prophecies remain unfulfilled. Americans quickly realised that a great boon had been extended to them, and, what was more to the point, proved that they were ready to pay the increased tariffs which were charged for berths in the new cars.

Mr. Pullman shared none of the fears which he heard expressed on many sides concerning the possibilities of his success, but devoted himself assiduously to even a higher standard of work than was seen in the "Pioneer." He succeeded in a degree beyond all expectation, but the next car cost twenty-four thousand dollars, or six thousand dollars more than its predecessor. At that time the price of a berth in the existing sleeping cars was $1.50. Mr. Pullman said that one in the new car ought not to be offered for less than two dollars. This proposal alarmed the President of the Michigan Central Railway, on which the car was to run, and it was feared by the Company that the imposition of the extra fifty cents would drive passengers to use competing routes. Mr. Pullman speedily solved the problem by proposing that the Company should run old and new cars in the same trains, so that passengers who did not care to pay more than the original tariff could travel in the old berths, while those who were prepared to give another fifty—cents might secure places in the new cars.

A single week's experience was sufficient to demonstrate that Mr. Pullman was right, and that the directors of the railway were wrong. On every journey the new cars ran without a vacant seat, while travellers positively refused to enter the old cars, and before very long they had to be removed from the service. Instead of diverting traffic to other lines, the Pullman cars became so popular, in fact, that they introduced a new element of competition, and rival railways were, one after the other, compelled to follow the example of the Michigan Central in providing accommodation far superior than that which had previously been seen. And the most remarkable feature of the revolution was that, owing to the influence exercised by the Pullman cars, the companies all round were able to fix their fares on a higher scale, which fully recouped them for the larger expenditure entailed by the construction of the new stock.

The Pullman Palace Car Company was organised in 1867, with the founder as President, and its cars were sent to every part of the American continent, the ingenuity of the designer culminating in the vestibuled train, which was first seen in the spring of 1887. The principle of the vestibule added immensely to the comfort of travelling long distances, and introduced an additional element of strength in construction which tended to secure the safety of passengers in case of collision. In the specification of his patent Mr. Pullman said: "The object of my invention is to provide suitable means whereby there may be made a continuous connection between contiguous ends of passenger railway cars, this connection being an entirely closed passage-way, preferably of the width of the car platforms, and serving at the same time as a vestibule for entrance and exit to the respective ends of the cars, the connection between the solid parts, forming a vestibule, being made of flexible or, adjustable material, so as to constitute a loose or flexible joint that will permit of sufficient movement of each unit car in travel, but at all times preserving a complete vestibule connection between the respective cars."

The first complete vestibule train ran in 1887 between Chicago and Jersey City on the Pennsylvania system, and such was its success that within eleven years similar trains have appeared upon no fewer than sixty-one different railroads in the United States, representing a total mileage of 91,000 miles. There have been many attempts to imitate the Pullman vestibule, but the original design has maintained its merits over all. It is so constructed that the flexible connection between the cars is self-adjusting. The face plates of the connections are pressed firmly together, whether the train be running on a straight road or round a curve, the pressure being evenly distributed by means of buffer springs fixed at the platform and also at the roof level. This frictional contact makes impossible the telescoping of one car by another in the event of collision.

In England, as also in America, the Pullman vestibule trains have been exposed to very serious accidents, but I am assured by those who have kept careful records of such occurrences, that in no instance has the telescoping of cars been known as the result of even the most violent impact. The accompanying photographs show the full extent of the damage caused to these trains in some of the most notable collisions. One of the worst accidents on an English railway was that which happened at Northallerton in May, 1894, to the East Coast Scotch express. The train, travelling at full speed on its journey south, ran into a mineral train which was being turned from the main line into a siding. Immense destruction followed, but although the train was well filled – its passengers including two Cabinet Ministers and the Deputy Chairman of the Great Northern Railway Company – the loss of life was almost nil. Not more than six persons were injured, and all but one recovered.

This remarkable escape from the terrible consequences that might have been anticipated was attributed by all the experts who inquired into the accident to the fortunate inclusion in the train of a Pullman car, the enormous strength of which saved the ordinary coaches in its rear. Similar results were noticed at an accident in the following year at Jackson, Michigan, in referring to which an American writer remarked that "of the five recent wrecks through rear collisions, had the trains been vestibuled, in every case but one the loss of life would not have occurred, and the destruction of the equipment would not have been one-tenth as great."

It was on the Midland system, between London and Bradford, that Pullman cars first ran in this country. This was in 1874, and the innovation was received with so much favour that the directors of the Company eventually came to have no fewer than thirty-five such cars in daily use. In 1888 the Company purchased the whole of these cars, and they have since run them as part of their own stock. The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway Company followed the lead of the Midland by introducing in 1875 a drawing-room Pullman in the Brighton service. Passengers were delighted with the splendid accommodation which the car afforded, and in 1881 a complete Pullman train – the first in England – began to travel daily between London and Brighton. Two other trains of the vestibule type have since been introduced, and at the present time the Brighton Company have eighteen Pullman cars at their command.

In America the standard length of each car is 75ft. over all, but the high platforms at British railway stations, when built otherwise than straight, obviously entail a considerable diminution in length, owing to the fact that the truss rods of the longest cars would came in contact with the edge of the platforms and the brickwork foundation. American railway stations, being without raised platforms, present no such difficulty. Hitherto the longest car made for use in this country has be 60ft. 8in.; but the Pullman Company are now constructing for the Brighton Company some vestibule cars which will be 63ft. 8in. over and this is probably the maximum length possible on our own railways. The Palace cars seen in the illustrations (pp. 380 and 381) were built for that Company in 1896, the materials being shipped to this country, and, in accordance with the practice always followed, put together under the superintendence of experienced workmen sent specially from the Pullman works. The London and South Western Railway Company have four similar cars running in their Bournemouth express service, and, in addition to those on the Midland and Great Northern systems, there are sleeping Pullman cars regularly travelling on the Highland Railway between Inverness and Perth.

One of the finest and most complete public trains in the world is undoubtedly "The New Pennsylvania, Limited," erected by the Pullman Company for use on the system of the Pennsylvania Railroad. It consists of parlour, smoking and library car, dining car, drawing-room sleeping cars, as well as compartment and observation cars. In point of massive framework, as much as in beauty of internal arrangement and decoration, the train marks a distinct advance upon all existing specimens of carriage building. Safety vestibules bring the whole train practically under a single roof 450 feet long. The forward section of the compartment and., observation car contains private state-rooms decorated either in Oriental or Louis XVI style, the fittings being alternately in Circassian walnut, Tabasco mahogany, English oak, vermilion wood, rosewood, or Santiago mahogany, while the upholstery, a bright floral pattern, was made expressly for the train. Each compartment has its own lavatory.

In the middle of the same car, between the compartment and observation divisions, there is a writing-room, containing secretaire and book-case, overhung by natural palms growing in pretty jardinières. Each train is accompanied by a skilled stenographer and typist, whose services may be secured, free of charge, by any passenger desiring to conduct correspondence en route. The observation room is lined with vermilion wood, and its plate-glass windows, nearly five feet in width, are the largest ever seen on any railway. There is no obstruction to mar the view from the recessed end, which is also chiefly composed of glass. The large open platform at the rear of the car is protected by nickel and brass guards, the space therein provided enabling twenty people or more to sit together in fine weather, enjoying the charming panoramic views through which the train passes. The drawing-room and sleeping cars are, like the dining cars, lined with mahogany, and both are exquisitely fitted. In the former, at each end, are double drawing-rooms, in which parties of from two to five persons can obtain privacy. The tables in the dining car are overhung by flowering plants, and the menu compares with that of a first-class hotel.

Another distinctive feature of "The New Pennsylvania, Limited," is a combination parlour, smoking, and library car, which provides a buffet, and all the luxury of an elegant, up-to-date club. There are daily papers, magazines, and books on the tables, and facilities are at hand for those who care to play cards, chess, or other games. Stock Exchange quotations are, with other items of commercial and general news, regularly supplied to the train at its stopping places. Passengers further have the advantage of a hairdressing saloon, and there are bath-rooms for ladies and gentlemen, equipped with all the most approved accessories. The train is lighted by electricity, the current being obtained from a dynamo supplying the 500 lamps comprised in the installation; but in order to guard against the possibility of a breakdown, Pintsch's gas fittings can at a moment's notice he brought into use in any of the compartments. Electric reading lamps are available in the library car and in the observation car, and every section of the drawing-room sleeping cars contains two such lamps, which may be used by passengers who desire to read in their private berths. The Pennsylvania Railway system, over which this magnificent train has daily been travelling since January 12th, 1898, extends from New York to Chicago – a distance of 913 miles – and there are connections, with drawing-room and sleeping-car accommodation, to Columbus, Cincinnati, Louisville, and St. Louis.

The advantages of travelling by Pullman car are made even more manifest in the long flight across the American Continent to California, the journey in fact becoming like a week's sojourn in a handsomely-appointed and comfortable hotel. From the solitary "Pioneer," the fleet of the Pullman Company has expanded until at the present time it numbers nearly 3,000 cars. The little village near Chicago where the great industry started has become Pullman City, with over 12,000 inhabitants, three-fourths of whom are employed in the building of the cars. Pleasantly situated near Lake Calumet, the town covers 3,500 acres. Originally the land was prairie; but Mr. Pullman drained it, and laid it out on a well-defined plan, from which experience has shown no necessity to depart. The sewage is collected and carried by pipes to the Pullman produce farm three miles away. The town has an excellent water supply, and produces its own gas. Included in its many handsome public buildings are several churches and chapels, a market house, large schools, a free library, a savings bank, a singularly well-appointed theatre, and an arcade in which the principal shops are grouped for general convenience. There are parks and pleasure spaces, athletic grounds, and tennis courts, and in every respect Pullman may be regarded as a model city.

The photograph here reproduced showing the Administration Building gives an idea of the scale on which the works were erected. They are capable of producing each year over 12,000 freight cars, 300 sleeping cars, 600 passenger cars, and nearly 1,000 street cars, representing a total length of more than 100 miles. The total amount of lumber used annually by the Company exceeds 51,000,000 feet, which would be sufficient to make a train of 5,000 cars, 35 miles long. Pullman cars every year carry between 5,000,000 and 6,000,000 passengers, and on an average nearly every passenger has, at least, one meal in the dining or breakfast cars. The longest regular and unbroken run of the cars is from Boston to Los Angeles – a distance of 4,322 miles. At the Pullman establishment workmen of all classes, including women and boys, earn $2.26 per day. There are 2,000 depositors in the savings bank at the works, the deposits amounting to $632,000, giving an average to each depositor of $316. All these facts go to show the thriving character of the great industry which has resulted from Mr. Pullman's zeal and enterprise.The European representative of the Pullman Company, Mr. John S. Marks, had had considerable experience of railways before he joined the service of the directors in 1874. For fifteen years he acted as conductor of the Pullman trains in this country, and thus became perfectly familiar with their successful working. When Mr. John Miller, the late manager of the Company in London, died in 1891, Mr. Marks was appointed to succeed him as manager and secretary, and the confidence reposed in him has since been further indicated by his nomination to a seat on the board of directors. A more enthusiastic champion than Mr. Marks the Pullman Company could not possibly secure. He cherishes with pride the records of the development of the Pullman Company, and at his offices under the roof of the London, Brighton and South Coast headquarters, at London Bridge, he has a collection of photographs which are almost alone sufficient to tell the interesting, story. There can be little doubt that Mr. Marks is well justified in claiming that Pullman cars have been chiefly instrumental in bringing about the very great improvement which has been witnessed in the character of passenger rolling stock in this country during the past quarter of a century, and he was naturally much amused the other day when one of the London daily newspapers gravely suggested that something unique was about to be accomplished by a southern line in introducing a breakfast car upon a particular part of its system. "Why, twenty years ago," said Mr. Marks, "the Great Northern Company ran a breakfast car. It was the first hotel car ever seen on an English railway. It was built by the Pullman Company to run between King's Cross and Leeds, and was soon followed by similar cars which we supplied to the Midland Company. In fact, everything that has been done in this country to provide hotel accommodation for railway passengers en route dates from the introduction of these cars."

— , "The Wanderer", , The Railway Magazine, , 1899